German domination über alles —

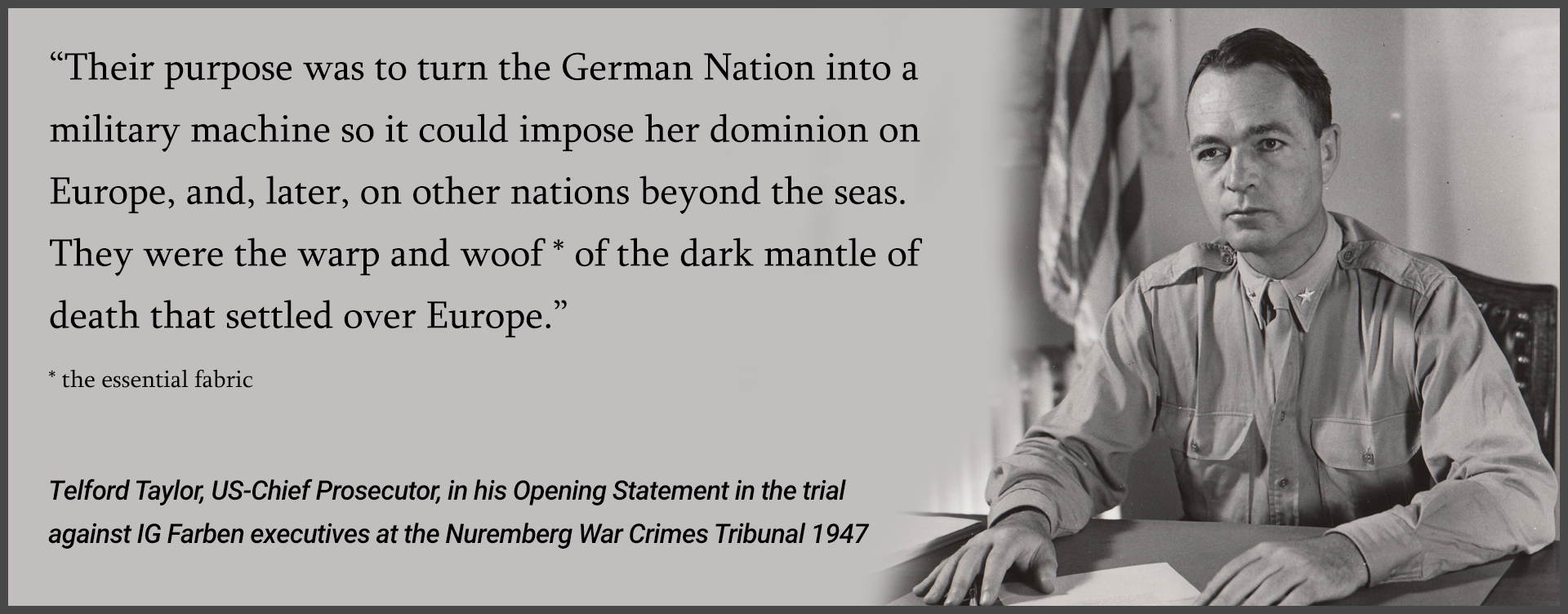

The cartel already existed before they signed the contract and made it official in 1925. Bayer’s Carl Duisberg and BASF’s Carl Bosch had been leading voices for the German chemical cartel, even before jointly establishing IG FARBEN. During World War I, Carl Duisberg had pressed for a widespread use of poison gas to aid the German conquest of Europe. Carl Bosch helped to develop the Haber-Bosch process and ensured that the German troops would have enough explosives in their joint quest for domination.

The German chemical giants informally worked together. Familiar patterns of market behavior were established in those early years and shaped during the 20th century. By the end of the Second World War, IG FARBEN would nominally have ceased to exist as a company. Yet its subsidiaries — Bayer, BASF and Hoechst — were led by the very same people who presided over IG FARBEN. Together they formed a new German state under their guidance, and they kept on working together informally, just as they had before they formed one giant corporation.

Colonel Bernard Bernstein prepared his report shortly after the war. It was officially published by the American government in 1945.

Bayer

Bayer’s CEO Carl Duisberg was the driving force behind the IG Farben merger and remained the most influential manager until his death.

BASF

The Nobel laureate Carl Bosch led BASF into IG Farben. Like Bayer and Hoechst, BASF held 27.4% of IG Farben’s shares.

Hoechst

Hoechst was the third big company to participate in IG Farben, although they initially declined to merge with BASF and Bayer

The decision to merge all German chemical companies into one giant trust had been born of greed and envy. While visiting America in the early 1910s, Carl Duisberg had been impressed by what he witnessed with Rockefeller’s Standard Oil. He saw a way to print money and to conquer the world with Germany’s unmatched strength in the chemical sector. Corporate agreements ensured that Rockefeller’s oil trust and the German chemical trust could grow globally without trespassing upon each other’s territory.

There was just one thing that threatened IG FARBEN’s profits: the first German experiment with democracy. The post-WWI, supposedly peaceful German state had no ambition for global domination. The powerful IG FARBEN board used the political turmoil in Germany after the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II, and became the largest donor to the openly undemocratic Nazi party of Adolf Hitler. Their investment paid off when IG FARBEN’s money propelled Hitler to power. World War II would not have been possible without them

Let us be clear: IG FARBEN was never forced to work with the Nazi regime. They were already working on plans for German world domination through chemical and pharmaceutical products before they used Hitler’s movement. Simply, their interests coincided. Carl Duisberg was promoting the idea of having a Führer two years before Hitler’s rise to power. IG FARBEN executives were in charge of the Four-Year-Plan office that boosted the war machine for Nazi-Germany — and which brought in immense profits for IG FARBEN.

Meanwhile, one of the most important links between state and industry was located at Berlin NW7, in IG FARBEN’s Berlin offices. Berlin NW7 not only took care of the company patents, but also coordinated the offices around the globe, kept in contact with politicians, and created the wish list of companies that IG FARBEN wanted to take over as soon as the German army invaded a new country. Berlin NW7 also acted as a secret service for Germany, locating targets for the bombs manufactured with explosives produced in IG FARBEN factories.

IG FARBEN was not only guilty of plundering. During wartime, a large part of the workforce of this giant corporation was made up of slave laborers and inmates of concentration camps. When the Nazis opened their first concentration camp, in Dachau, just weeks after their rise to power in 1933, IG FARBEN icon Carl Bosch immediately welcomed the idea. Later, an IG FARBEN company produced the poison gas Zyklon B that was used to kill the inmates of the concentration camps. But it was another concentration camp that showed the full scope of IG FARBEN’s involvement.

Auschwitz was one of the biggest extermination camps in human history. Millions of people were killed in the gas chambers. However, that was not the sole reason for its existence. IG FARBEN built a giant factory directly next to the concentration camp and used the inmates as cheap laborers there to produce Buna, the artificial rubber used by the German army. IG FARBEN executives were directly involved in the planning of the Auschwitz concentration camp and were sentenced at Nuremberg for it.

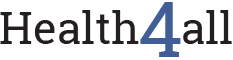

The Nuremberg Tribunal against 24 managers of IG FARBEN was historic. It was the first trial directed at industry leaders of a private company. During the tribunal, it was evident that, without IG FARBEN, Hitler’s conquest war would not have been possible. As important as this tribunal was, the aftermath was disappointing, to put it mildly. The managers were sentenced, but – compared with other tribunals – the outcome was too trivial. None of the accused would be in prison for longer than a few years.

By the early 1950s, with IG FARBEN separated into its three subsidiaries, BAYER, BASF, and HOECHST, all of the former IG FARBEN managers were back in leading roles in their companies, and, informally, they began once more to work together. Even their system of establishing contacts among the highest ranks of German politics was re-established. One of the most prominent historical figures to be implicated was Helmut Kohl, German chancellor from 1982 to 1998. But he was far from being the only one to come under the influence.